|

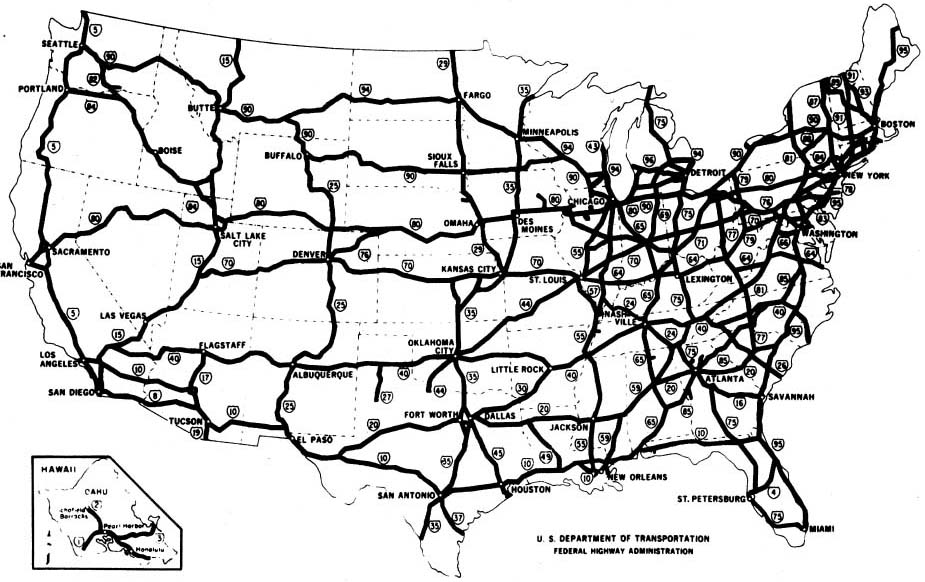

| 1956 Map of Eisenhower Highway System |

Someone should start preparing the

eulogy for publicly operated, built, and financed roads. The era of government grants, shovel-ready

projects, and pork-barrel politics is coming to an end, and, like anyone

overstaying their welcome, it’s taking much longer than is appropriate to say

goodbye. I believe that the construction

of a standardized, integrated 41,000+ (Roth 2010)

mile national highway system could only be possible with the massive amount of

capital and funding provided by the federal government. However, with the completion of the highway

system near the turn of the century, the era of mega-scale public works

projects is waning, replaced, in part, with the bothersome and costly task of

adequately maintaining and operating that infrastructure. In addition to states deferring routine

highway maintenance in hopes that the federal government will simply replace it

(Semmens 2012) , there are issues with lobbyists and

special interest groups impractically influencing the funding and revenue

streams; inefficiencies and waste with

multi-level government planning; and over-regulated systems that discourage any

kind of innovative cost-saving practices (Roth 2010) . In contrast, private entities won’t build a

project unless they see a return in it, i.e. unless it makes economic sense,

and their relatively smaller size allows for more customized solutions that

better represent the needs and behaviors of the users.

|

| The Lee Roy Selmon Crosstown Expressway, a high-occupancy toll lanes project in Tampa, Fla., is shown completed and in use. The $420 million, 10-mile elevated tollway was built by private investors. |

In his review of Clifford Winston’s

Last Exit: Privatization and Deregulation of the U.S. Transportation System,

John Semmens summarizes the author’s critiques of government run transportation

with phrases like “undermines efficiency,” “ballooned… operating deficits,”

“politics overrides economics,” and “irrational user-tax policies.” (Semmens 2012) The main critique, out of which the majority

of problems arise, is simply the way in which roads are currently taxed and how

the funds revenues from which are handled.

The revenue from gas taxes, historically the bulk of federal highway

funding, has progressively lost its purchasing power due to a combination of

increased construction costs and a decades-long unwillingness to increase

the tax. A 2011 report from the

Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy attributes these factors as causing a

20% decrease in the real value of States’ rates and a 41% decrease in federal

since the last gas tax increase. Add to these ear-marks for

low-priority projects (Bridge to Nowhere), ever expanding state budget-gaps,

and “half of the states [being] shortchanged by the current

highway trust fund allocations” (Roth 2010) , there is a strong

case for a change in road management.

|

| Chicago Skyway privatized in 2004. |

Kenneth Small listed out

in his article Urban Transportation Policy: A Guide and Road Map three

ways which private companies are better suited for road operation and

management. First, as mentioned before,

private companies are not going to invest in something from which they don’t

foresee a profit or which will sink them in debt. Thus, fiscal and economic feasibility of any

project they endeavor to take on will be thoroughly researched. This logically translates as providing services

for which the community demands, meaning a more satisfied constituency. Secondly private companies are more

experienced with “price

sensitivity, public perceptions, marketing, and the roll of price

differentiation.” Experience is

important. A U.S. PIRG Education Fund report

acknowledges that privatization is a good choice when a private company has a “proven

comparative advantage over government agencies in providing a particular good or

service.”(Baxandall 2009) Not being

enmeshed (though still not entirely immune) in the politics of road use is one

of those comparative advantages that would mean faster and more customizable

service. Thirdly Small writes that a

by-product of pursuing a profit is a constant desire for more efficiency, on

the road and in the office. “It is well known in the academic

literature that a private road operator, even one with a monopoly, will choose

to differentiate prices by time of day in a manner very similar to that called

for by standard congestion pricing recommendations.”

|

| A failed privatized toll road in Brisbane, Austrailia |

Admittedly there are

risks and downsides to privatizing transportation infrastructure. In the same U.S. PIRG report mentioned above,

author Baxandall lists some of the pitfalls that can accompany these deals. Non-compete clauses have metaphorically bound

the hands of the government in their efforts to improve neighboring public

highways seeing that those improvements would take business away from the

private company. Long term leases, 75

and 99 years, are far too long for legislators to be able to predict the needs

of the populace. There is also a lack of

transparency, the public not getting the full value of the road, and always a

fear of inequity. Some of these issues

can be addressed through smarter contracts, shorter leases, and more oversight,

while better management of spending and innovation is needed to solve others

like the equity problem. The fact

remains that governments are struggling to adequately manage their existing

assets and the budget gaps seem to get bigger every year. While privatization poses both risks and

advantages, I believe the latter outweighs the former.

Good-bye crumbling,

out-of-date infrastructure. Rest in

peace.

- Baxandall, Phineas, “Privatre Roads, Public Costs,” 2009. http://cdn.publicinterestnetwork.org/assets/H5Ql0NcoPVeVJwymwlURRw/Private-Roads-Public-Costs.pdf

- Roth, Gabriel, "Federal Highway Funding," 2010. http://www.downsizinggovernment.org/transportation/federal-highway-funding

- Small, Kenneth, "Urban Transportation Policy: A Guide and Roadmap," 2007. http://www.economics.uci.edu/files/economics/docs/workingpapers/2006-07/Small-24.pdf

- Semmens, John. 2012. "Last Exit: Privatization and Deregulation of the U.S. Transportation System." The Independent Review Vol. 16 Issue 3, p 456-460.

Provocative post, thanks!

ReplyDeleteI wonder, do you see privatization affecting the road network at all scales of operation?

It seems like, to date, privatization efforts have mostly been attracted to capital-heavy, linchpin infrastructure (such as bridges, or less frequently expressways) that offers a well-defined return and large market. There are also many examples of local road infrastructure being privately financed and operated, but this is usually within some other revenue-generating enterprise (ie, developers creating roads in their subdivisions, or Disney's privately operated village).

It seems that privatization does not fit as well with everything in-between, such as local collectors or arterials. It may be a more attractive prospect for private investment if road-specific vmt charges were in place, but without that such projects seem to offer little return on investment.

My feeling is that we're moving toward some sort of fusion, where governments maintain their role in regional and local planning and implementation. This would be complemented by PPP arrangements for capital-heavy projects, where governments may set requirements but ultimately leave implementation to someone else.

One of the problems of privatization is that the private companies will cherry pick the best places to be and leave the rest to the government unless there is some major incentives to get them to agree to take on the roads with lesser opportunites. While it is clear as our infrastructure continues to age and there is less money to fix it, some changes are going to have to be made.

ReplyDeleteThe question would be what happens to highways in the rural part of the country. We have some roads (such as Interstate 15 north of Idaho Falls, Idaho; Interstates 90 and 94 east of Billings, MT that don't even have enough traffic on them to justify them being Interstate highways. What happens to these roads?

Further if we privitize the road system will those private companies will also fight against anything that will take money away from them including alternative forms of transportation.

Going to Ben's point, where do we draw the line between the responsibility of government to the citizens and then need to find alternative ways to finance projects?

I do not advocate for the entire road system to be privatized. In order for privatization to work there needs to be some kind of profit, and neighborhood roads, arterials, and highways in the hinterland aren't going to provide that. I'm imagining that privatization would work on a megaproject scale: large toll highways and bridges (the CRC perhaps). This is what brings in the money and would be the projects that private companies would, very logically, cherry pick. If I was in the business I'd look for the lucrative options rather than the paltry ones.

ReplyDeleteBut, if you can imagine just getting some of these mega projects off the ledger sheet, the state or city could save that money and put it toward the betterment of the network. This brings up John's point about the companies discouraging alternative modes of transit. This was one of the issues brought up in the PIRG report: non-compete clauses make it very difficult to improve surrounding, "competing" roadways. These clauses should be nixed. Not even allowed on the table. However I think it's smart to treat the owner and operator of a crucial piece of the network as a partner rather than your competition. If you drive that guy out of business, than your stuck with the big expensive road again. Perhaps some innovative policy solutions for this kind of PPP are out there.

I just don't know how else the nation can catch up on its infrastructure needs. My co-worker said that not spending six trillion dollars on a war is a good start, but I don't think war mongering will be affected by the sequestration. Ben, I'm not familiar with road-specific VMT charges. How would a private company reap the benefits of these?

Check out the Chicago Skyway project. It is unique in that even though it is privately run, maintained, and all revenues go back to the private company the city still owns it.